High flows on the San Joaquin River in 2023 (Florence Low & CA DWR)

by Sustainable Conservation and Earth Genome

The San Joaquin Valley sits at the crossroads of California’s water challenges. It produces a quarter of the entire nation’s food (including 40% of its fruits and nuts), but excessive groundwater pumping is causing the ground to sink up to a foot per year in some places, buckling roads and canals. Extreme droughts exacerbate community water insecurity and put the region’s native fish at risk of extinction, but when it does rain, the flooding puts over two million people’s homes at risk. These existing water management challenges will be exacerbated by the effects of climate change. In this complex landscape, the Merced River Watershed Flood-MAR Reconnaissance Study is a model for how science, collaboration, and forward-thinking water management can drive real-world change.

Figure 1 – The Merced River Watershed Study Area

From Study to Strategy

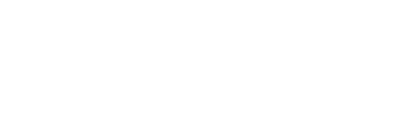

When the California Department of Water Resources (DWR) and Merced Irrigation District (MID) launched the study in 2021, the goal wasn’t just academic. They set out to answer a pressing question: how can this watershed adapt to climate extremes in a way that benefits farms, communities, and the environment? The three-year study used a cutting-edge climate vulnerability assessment to determine the baseline climate risk, then modeled different adaptation strategies to see what effects they would have on water supply, flood risk, and habitat. One of the key adaptation strategies considered in the study is Flood-Managed Aquifer Recharge (Flood-MAR), which diverts floodwaters to recharge groundwater supplies, capturing some of that excess flow in our aquifers for future use. Essentially, Flood-MAR uses the aquifer as an underground reservoir that increases the total storage capacity of the watershed. While this practice alone cannot solve the water crisis, the study found that combining it with Forecast-Informed Reservoir Operations (FIRO) and strategic infrastructure investment can achieve a 40% to 60% reduction in groundwater overdraft. Pairing these strategies and investments with targeted recharge demonstrates that where recharge is done matters. In the study, recharge was prioritized in certain areas to provide meaningful outcomes for subsidence mitigation, drinking water supply improvement, flood risk reduction, and ecosystem support.

Figure 2 – Groundwater overdraft under each adaptation strategy

The Role of GRAT

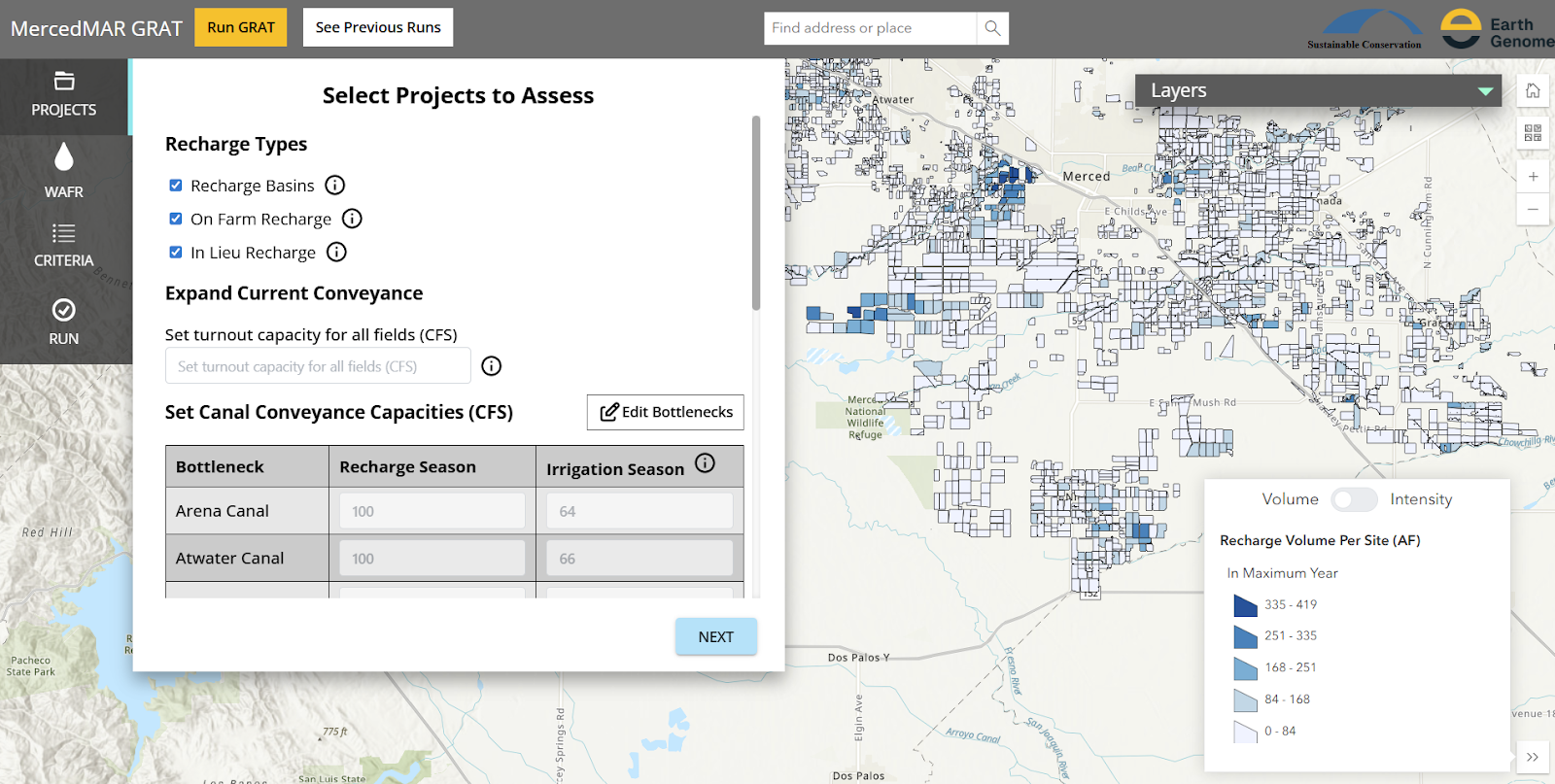

To determine the amount of recharge that is possible under each of the different scenarios, DWR relied on the Groundwater Recharge Assessment Tool (GRAT), developed by Earth Genome and Sustainable Conservation (see Figure 3). GRAT is an optimization model that evaluates recharge strategies given a set of constraints and goals. It considers water availability, conveyance capacity, crop compatibility, and socioecological management objectives—placing recharge water where it will maximize benefits while minimizing costs. Irrigation districts have been using GRAT since 2017 to determine which fields to include in their recharge programs.

For this study, GRAT was used to model what it would look like if all the MID farmers came together to turn a potential hazard (floodwater) into a shared benefit (groundwater storage). This includes filling the canal system in the winter to increase seepage, operating dedicated recharge basins, and even flooding their farms, with GRAT’s crop compatibility calendar ensuring that the on-farm recharge doesn’t harm the crops.

On-farm recharge proved to be a key strategy, with the potential to recharge more water into the aquifer than the canals and recharge basins combined. Because there are no commercial hydrologic models that incorporate Flood-MAR as a practice, GRAT is crucial to understanding the role Flood-MAR plays in climate adaptation.

Figure 3 – Interface for running GRAT

How the Study is Being Used Today

What’s Next?

This isn’t just about one watershed. The Merced study represents a shift toward integrated, climate-smart water management in California. It’s about connecting local projects with regional strategies, blending green infrastructure with grey infrastructure, and preparing for a future where flexibility and foresight are essential. As outlined in the California Water Plan Update 2023, DWR will use this study to inform the 2027 update of the Central Valley Flood Protection Plan and will work with other local partners and regional agencies, including the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes, to complete similar studies for additional San Joaquin Valley watersheds. Studies on the Calaveras, Stanislaus, Tuolumne, and Upper San Joaquin watersheds have just been completed and DWR plans to release these reports in 2026.