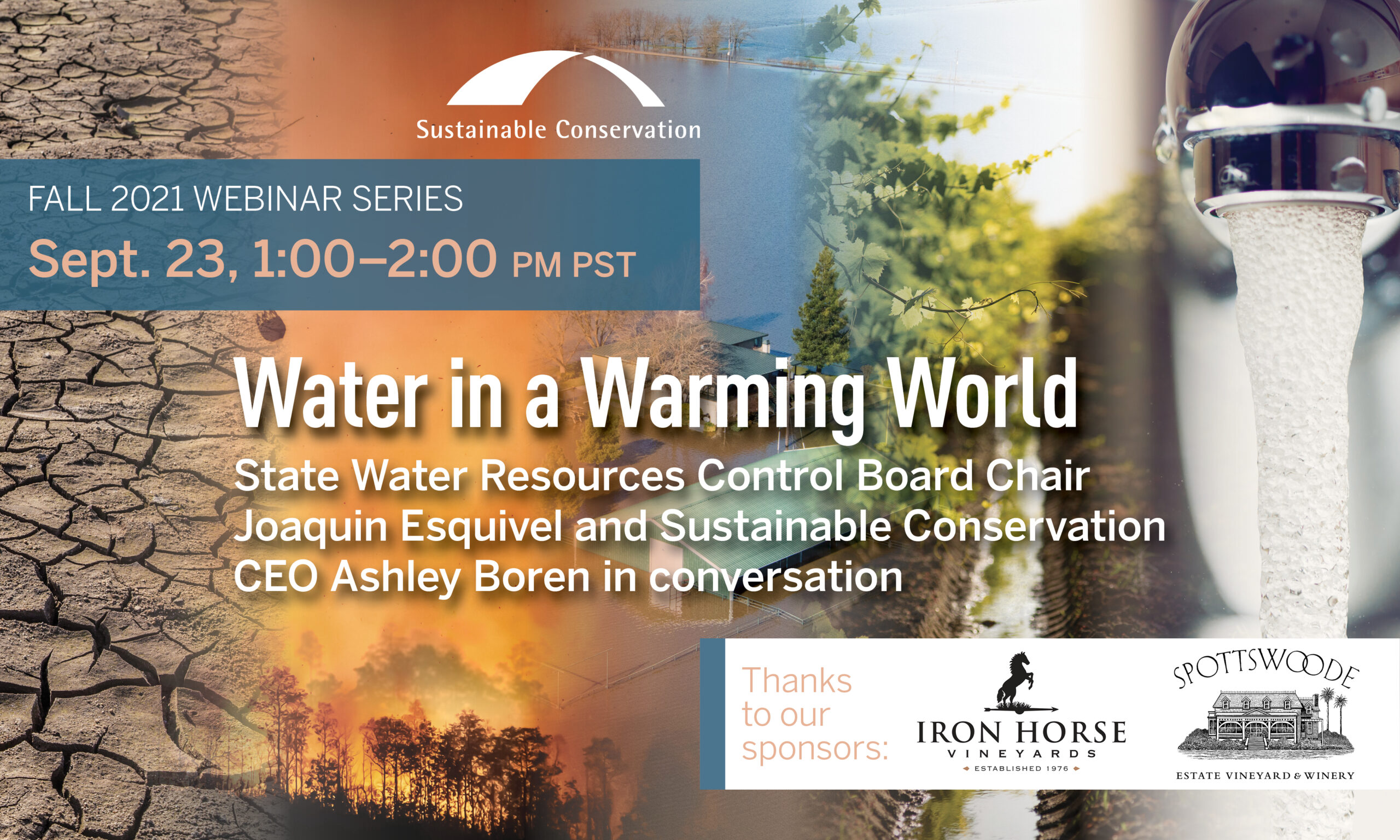

We kicked off our fall webinar series last month with a great conversation between CEO Ashley Boren and E. Joaquin Esquivel of the California State Water Resources Control Board.

You all had so many amazing questions that we couldn’t fit into our time with Joaquin, so we pooled our staff’s brainpower for some answers. Read on for some policy deep dives, floodplain facts and where to go for more information on all things California water.

What is actually being done to save water from the rain, when it comes?

Ashley Boren, CEO: Beyond the above ground reservoir system in California, a number of regions have groundwater recharge basins and/or spreading ponds to capture water in heavy rainfall or snowmelt years. The San Joaquin Valley uses recharge basins like the one in this photo and Southern California uses spreading ponds like the photo on the upper right of this link. Having said this, there is a realization with the increasing frequency and severity of droughts that when water is available California needs to do more groundwater recharge than it has been doing in the past. Water agencies are building more recharge basins, and exploring other methods for groundwater recharge like the methods Sustainable Conservation in promoting including restoring floodplains and using fallow and active farmland to recharge groundwater.

Ashley Boren, CEO: Beyond the above ground reservoir system in California, a number of regions have groundwater recharge basins and/or spreading ponds to capture water in heavy rainfall or snowmelt years. The San Joaquin Valley uses recharge basins like the one in this photo and Southern California uses spreading ponds like the photo on the upper right of this link. Having said this, there is a realization with the increasing frequency and severity of droughts that when water is available California needs to do more groundwater recharge than it has been doing in the past. Water agencies are building more recharge basins, and exploring other methods for groundwater recharge like the methods Sustainable Conservation in promoting including restoring floodplains and using fallow and active farmland to recharge groundwater.

Can you give us an update on the Safe and Affordable Funding for Equity and Resilience (SAFER) program and its impact on providing safe and clean water to rural communities and underserved communities of color?

Charles Delgado, Policy Director: The Water Board has recently adopted guidelines for its Water and Wastewater Arrearage Program, which will be run through SAFER. This will direct funding received through this year’s budget to address COVID emergency-related utilities arrearages run up by low-income water users and to support water providers in disadvantaged communities.

Charles Delgado, Policy Director: The Water Board has recently adopted guidelines for its Water and Wastewater Arrearage Program, which will be run through SAFER. This will direct funding received through this year’s budget to address COVID emergency-related utilities arrearages run up by low-income water users and to support water providers in disadvantaged communities.

SAFER put on a webinar in late October to begin workshopping its updated map of high-risk aquifers, the tool that it uses to prioritize clean drinking water projects and assistance. The 2022 map is planned for release in January.

The Board has recently initiated the mandatory consolidation process to improve water service in the City of Exeter, and is currently overseeing third-party administrators in 13 districts, serving approximately 1,000 service connections that provide water to approximately 3300 residents.

The FY 2021-22 SAFER Fund Expenditure Plan contains information about which drinking water infrastructure, technical assistance, and operations & maintenance projects have been prioritized for the duration of the fiscal year, and may be viewed here.

How can we reconnect or restore the natural floodplains and recharge our aquifers before it’s too late?

Aysha Massell, Water Program Director: This is a very fruitful avenue to pursue. Floodplains are key to healthy riparian systems and provide so many benefits, including flood risk reduction, valuable ecosystem habitat, improved water quality, and even groundwater recharge. This last benefit is an active area of research right now, and there is still a lot to learn in terms of how we can predict the amount and fate of recharged water that occurs from floodplain inundation. There is a growing community of people, organizations and agencies that are working on research related to floodplains, as well as making floodplain restoration projects easier to implement by providing funding, improving the permitting process and building and monitoring projects.

Aysha Massell, Water Program Director: This is a very fruitful avenue to pursue. Floodplains are key to healthy riparian systems and provide so many benefits, including flood risk reduction, valuable ecosystem habitat, improved water quality, and even groundwater recharge. This last benefit is an active area of research right now, and there is still a lot to learn in terms of how we can predict the amount and fate of recharged water that occurs from floodplain inundation. There is a growing community of people, organizations and agencies that are working on research related to floodplains, as well as making floodplain restoration projects easier to implement by providing funding, improving the permitting process and building and monitoring projects.

Given the scope of the drought and the increasing climate impacts generally, is it time to require all basins to initiate the Groundwater Sustainability Plan (GSP) process?

Charles Delgado: The drought emergency has once again demonstrated the need for California to have robust data-gathering and planning infrastructure to manage its water supplies. While we need more information before determining whether all basins should initiate the GSP process, it is clear that more will need to be done, in SGMA and beyond, to ensure a sustainable water supply.

Would it be constructive to systematically and comprehensively revise California water law? If so, would that be feasible?

Charles Delgado: Substantive reforms to California water rights law would be beneficial. The current system has its roots in the Gold Rush, and was primarily codified in 1914 and 1967. This has resulted in a water rights structure that is rooted in historical uses and practices of a much different era, persisting into the present. The current system is ill-equipped to respond to the present-day realities of drought, climate change, and increasing economic pressures on municipalities, agriculture, the environment, and all of the users of water in California.

There are a number of aspects of the water rights system that need to be improved; proper accounting for water scarcity now and in the future, the ability to capture and allocate flood flows, easing transfers, proper data infrastructure, and others. Any comprehensive solution must be developed as part of a cooperative process with water users, government agencies at the state, federal, and local levels, and advocates for the environment and affected communities. While this may be a difficult process, positive change is definitely possible with the commitment of the state’s water stakeholders.

Is California agriculture changing produce crops to ones that need less water?

Ashley Boren: Farmers are moving to crops where they can get more economic value for each drop of water used. This has meant farmers in California have moved from growing cotton and wheat to growing nut crops and almonds.

Why is local water control so important? Doesn’t it need to be top-down?

Charles Delgado: Any decision-making process involving water in California must have at least a component of local input. While the entire state faces the challenge of historic drought conditions, each region has its own specific issues. Some regions contend with immediate drinking water supply emergencies. Some are impaired by seawater intrusion into groundwater basins. Some are adapting to a future where surface water irrigation is no longer a reliable option for agriculture. Some must combat extensive land subsidence resulting from depleted aquifers. Many face a combination of these and additional challenges. The water managers and community leaders in local regions are the most knowledgeable persons as to what problems affect their communities, and what the potential solutions are.

Local expertise is recognized as an invaluable resource throughout the state’s water oversight structure; this is reflected in the groundwater basin-based approach of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, the watershed-based boundaries of the Regional Water Boards, the network of local Division of Drinking Water offices, and many other programs. State guidance can be a powerful tool for positive change. But local knowledge, possessed by community members, local governments, Native American tribes, environmental advocates, and other stakeholders, should always inform any policy approach.

How can we keep up with what is happening, how water plans develop and what is actually being done in CA?

Ashley Boren: As Joaquin mentioned, the State Water Board works to keep their website (and drought page) up to date. Many of us also subscribe to Maven’s Notebook which compiles the water related news from many publications on a daily basis.