Missed the latest webinar in our Climate Resilience from the Ground Up series? We’ve got you covered with a recap of the event, and you can watch the full recording now! As always, many thanks to our generous webinar series sponsors: ESA, Holland & Knight, Iron Horse Vineyards, and Spottswoode Estate Vineyard and Winery.

Sustainable Conservation Water for the Future Program Director Aysha Massell moderated an excellent panel of climate experts, including the Honorable Ron Goode, Chairman of the North Fork Mono Tribe; Julie Rentner, President of River Partners; and Dr. Daniel Mountjoy, Director of Resource Stewardship at Sustainable Conservation.

California’s climate extremes are fueling what feels like a never-ending cycle of flood, drought, and fire across our entire state. These conditions aren’t anything new in our long ecological history, but their intensity is. How can we adapt to these new realities of climate change?

The North Fork Mono Tribe and Land Management

Chairman Goode opened our discussion with an overview of our drought history – noting that we’ve experienced two megadroughts since around 400 A.D., and that they’re part of our history and Mother Nature. As our drought cycle intensifies, it still takes two years for the state to be able to officially declare a drought emergency. When it comes to wildfires, we need new strategies and practices to help us weather warming temperatures, tree die-off, bark beetle infestations, and an ever-growing, drought-fueled fuel load in our forests.

The North Fork Mono have lived in the Sierra for thousands of years. Before European migration, land seizure, and forced relocation, there were over 350,000 Tribal members. Before the 1800s, around 40% of our forests in the mountains were in canopy, and the trails all over the mountains were clear.

“Our people have survived and moved through all the conditions that’ve been thrown at us – including the intrusion of Euro-Americans and others who changed our backyards, our culture, and our way of life.” – Chairman Ron Goode

Now, due in large part to the suppression of Indigenous land management and forced relocation of the Mono and other Tribal people, 80-90% of our forest is in canopy. Chairman Goode notes that keeping people off the land and prohibiting them from managing forests leads to this outcome. In addition, animals made use of these previously open trails and less dense forested areas to flee fire. Now, they’ve taught their babies how to hide – and when they hide, they perish.

“It’s About Renewal”

Chairman Goode walked us through the differences between prescribed burning, or burns that focus on acreage, burn higher on the land, and can often lead to out-of-control fires, and cultural burning, or low-to-the-ground, closely monitored burns on carefully prepared land with holistic forest renewal in mind.

“Cultural burning is about renewal. Prescribed fires aren’t about a sustainable forest – they’re about acreage. When we put fire on the land for cultural burning, we expect our resources to return in one or two months. We want that regrowth, and it’ll take 6-8 years in a live, thinned-out state where it’ll hold water higher in the soil.” – Chairman Ron Goode

Prescribed burning tends to burn hotter, which can destroy tree root systems. Cultural burns are managed during and after the practice, as people rake the soil, redistribute the ash as a soil nutrient, and the land can recover. An interesting fact: there may not be a “record” of these burns in the past because the land was maintained, and they never burned high enough to char tree bark or appear in the tree rings that we use as living timelines of climate events, prior catastrophes, and seismic ecological shifts.

“There is hope.”

Julie Rentner next walked us through the amazing floodplain restoration that River Partners and other organizations are doing in the San Joaquin Valley, noting the similarities between large-scale burning and other ways in which forests and floodplains can be restored and managed so habitat can flourish.

These dry spots are actually floodplains that can “flex” into critical riparian habitat when flows are low, and take on more water for a wider, slower river when flows are high. Photo: Julie Rentner, River Partners.

The San Joaquin Valley is a growing hotspot for extreme flood events, as channelized and levied rivers carry the result of heavy precipitation events – high flows – further and further downstream. This adds up to poor river habitat, dwindling groundwater levels, and serious community peril. River Partners’ project at Dos Rios Ranch – soon to be a state park! – is a fantastic example of how letting nature do what it does best benefits us all.

“Hydrologic swings in the Valley are terrifying. Our productive agricultural economy, and the people who depend on it, are at risk. When we do floodplain restoration, we’re not talking about breaching a levy and spreading water haphazardly – this is a highly engineered, careful change. After 15 years of doing this work I can say the hope should be there. We can do this. ” – Julie Rentner

Reconnecting historic floodplains means rivers can spread out, slow down, and improve our water quality, recreation, wildlife outcomes, ecosystem recovery, and flood safety. Floodplains are part of a river, not outside of it, and as they flex in dry times they can support riparian habitat, and even flood-compatible farming. They’re rich habitat for stressed species, and we need sustained investment to maintain these critical areas – and connect people to both the land and meaningful stewardship.

“The Middle Ground”

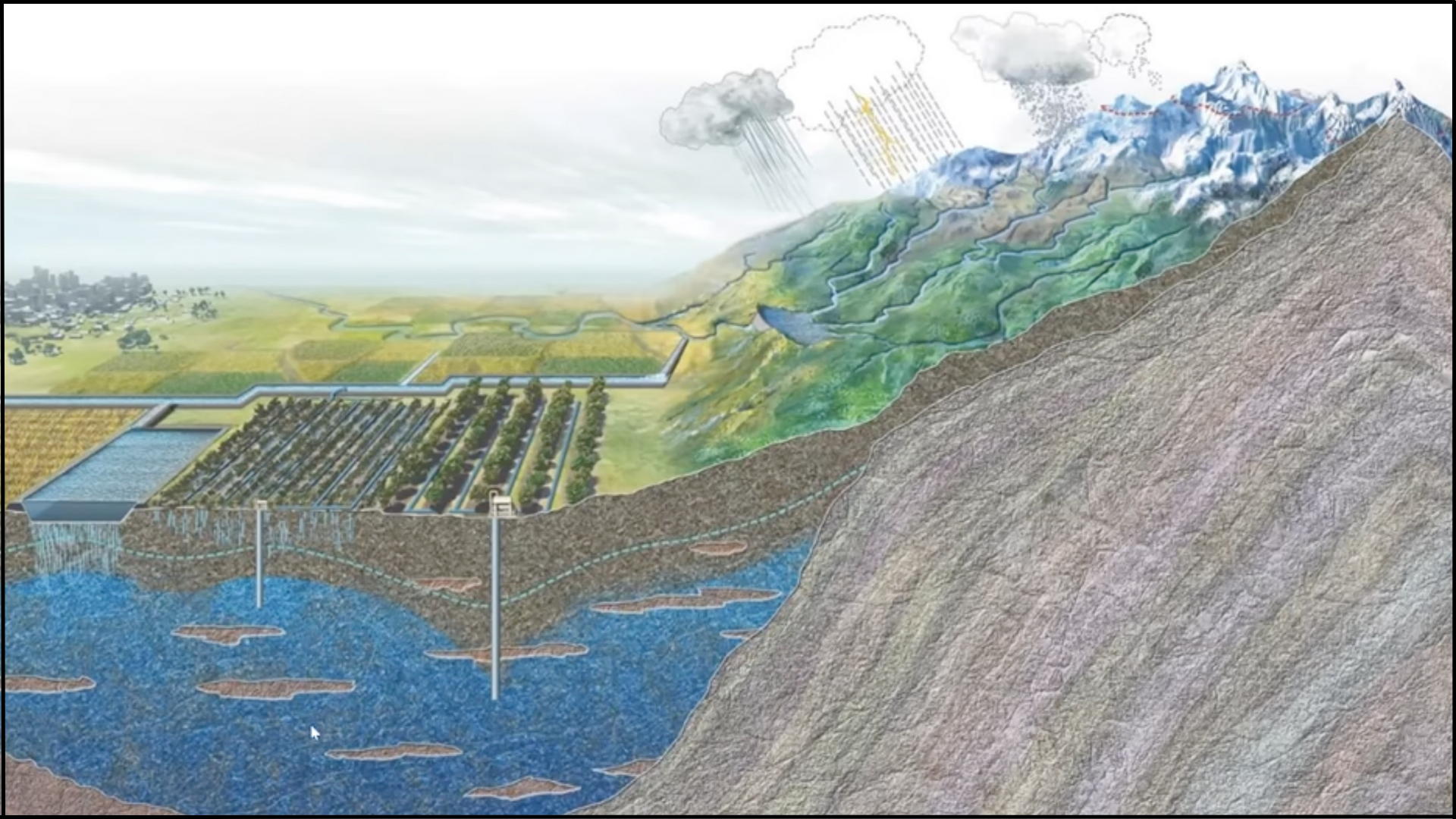

Dr. Daniel Mountjoy noted that Sustainable Conservation’s work is situated primarily in the human-settled, productive valleys and foothills that produce our food and support a large population in California. When Europeans arrived, we dramatically altered the footprint and hydrology of what once was one massive floodplain in the San Joaquin Valley. We built towns along rivers to access the water, and levied our rivers to protect ourselves from floods, and our farmland from damage.

These barriers mean our groundwater levels have dropped for decades, with serious consequences for communities, including threats to water security and drinking water quality.

With extreme storm events and more droughts in our climate future, we need to be able to capture water when it’s available, spread it out with existing canal infrastructure onto the agricultural landscape, and store it for when it’s needed during future dry periods.

As our precipitation future changes, so too must our strategies for capturing water when we can to secure our water future.

Our decade-plus of experience testing, siting, and promoting groundwater recharge falls in line with the California Department of Water Resources’ (DWR) Flood-MAR (Managed Aquifer Recharge) efforts, and irrigation and water managers’ increasing interest in groundwater replenishment. Flood planning and the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act have been key drivers of this culture shift, too.

Targeting recharge means more than just spreading it on fields that are available – we can site groundwater projects that also create migratory bird habitat, raise the water table in key riparian areas, and/or are in the vicinity of communities with wells running dry. We can help prevent further subsidence and infrastructure damage, and even have a beneficial effect on drinking water quality over time (and with careful management.)

“We have to work together, and partnerships are essential. We have to work with growers, land managers, irrigation districts, and agencies that are doing the permitting of this work to introduce the science of what’s underground, and our changing hydrology and climate realities for better state planning.” – Dr. Daniel Mountjoy

Our Merced River Watershed study with DWR cued up exciting potential for the area: with expanding conveyance, changing reservoir operation and on-farm recharge, we could mitigate up to 63% of the region’s annual overdraft and reduce flood flows by up to 65%. This information is fueling an expansion of this work into four additional watersheds – stay tuned for more on this effort soon!

What’s Next?

Stick with us, and take some solace in the truth that though our climate future will be a challenge, we can and are crafting collaborative solutions to weather fires, floods, and droughts.

Bringing people together is what we do, and we encourage you to visit our Check In & Connect page for access to all of our event recordings, and so you can catch up on any webinars you’ve missed. You can also check out our Twitter coverage of this event.